“Covid-19 has been a catalyst to data innovation” is a phrase that has been thrown around very often by many (I know I have); but how far do real-world experiences support this statement?

Covid-19 intensified the urgent need for timely data and information for decision making, with data playing an important role in policies relating to disease surveillance, health and relief resources allocation and prioritization, cases and mortality prediction, amongst other areas. Drawing from real-world examples of the use of data science in the Covid-19 response, in this article, I review the strategies that made data use for Covid-19 a lot more possible than we have seen before.

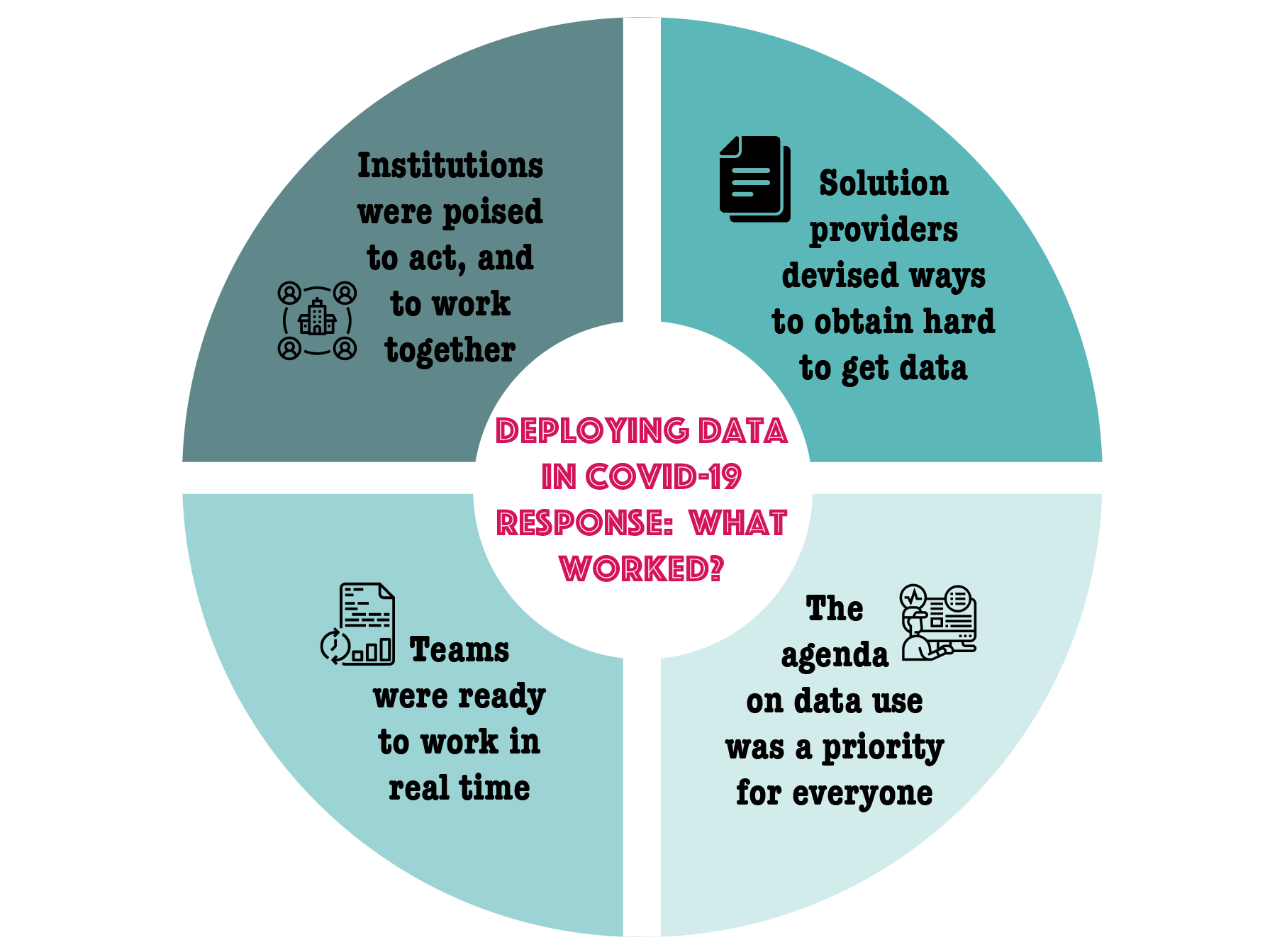

Institutions were poised to act and to work together.

The urgency of the pandemic meant organizations of all types were poised to take on new roles and work in new ways, creating a demand for data-enabled innovations. There was a clear and immediate need for reliable and timely data. Organizations like the Global Partnership for Sustainable Development Data (GPSDD) played a huge role in initiating and establishing grounds for data partnerships and were a catalyst for many governments aided data-driven solutions. GPSDD approached several national statistical offices in Africa and convened various actors (from policy, data providers, analysts and others), to help get new projects off the ground. Working across organisations in this way helped identify data needs and challenges that different national statistical offices were facing, exploring data access possibilities and bringing other partners on board for the analysis to happen. As a result, new coalitions were mobilized to help in identifying what data was available, what was missing, and who could fill the gaps. New partnerships were set up with relevant institutions, e.g. Centre for Disease Controls (CDC), to request access to data. The willingness with which national statistical offices and partners engaged with organizations like GPSDD to explore and uncover their data needs and challenges resulted in the analysis being possible faster than it would have been in a different case.

Other factors that made these collaborations and solutions successful included mechanisms for sharing data routinely rather than once, data harmonization, and the subsidized or no cost for Covid-19 dashboards (zero-rating data dashboards that can receive data from users). Case studies show that collaborations were more straightforward and faster where there were pre-existing relationships on the country level. Having already established engagements between various actors like local authorities, NGOs and other solution providers served as a good foundation for the analysis to occur quickly.

Data science solution providers devised alternative ways to obtain hard to get data that was in any way programmable.

Access to data has been a challenge, especially in the early stages of the pandemic. In many cases, absence of Covid-19 health data and data incompleteness made data analytics hard. Nevertheless, data scientists devised ways to gather supplementary data, for example, through weekly social media surveys distributed for people to share information about their symptoms, whether they had taken a Covid-19 test or not, and the test results. In another case, it became popular that health ministries in many countries shared Covid-19 status reports on their websites and/or social media pages for the public in pdfs and static images. With these, data scientists could conduct the extra work of turning this data into analyzable formats. With such alternative approaches, data analytics was made possible.

The reality is that most data is not curated and organized in ways that make it accessible or usable to decision-makers and other policy stakeholders. Practitioners in private and public sectors are not collecting and managing data with awareness and plan for broader retrieval or analysis beyond the initially intended task. For Covid-19 response, data scientists worked out ways around these issues to make evidence-based predictions, prioritization and overall decision making possible for the pandemic response.

Teams were ready to work in real-time.

The Covid-19 emergency, like any emergency response, required swift actions that could not wait to follow the standard data science project life-cycle. Responders needed insights quickly, and everyone was under pressure to deliver, especially decision-makers. As a result, responders sought interventions that could be rapidly implemented without compromising on the status of the data analytics. In this case, teams had to do the “intensive human tasks” (for example, manually making sure data is relevant and accurate instead of creating and training models that might require more data and time) to ensure getting results in real-time.

In addition, teams quickly adapted to different reporting structures as long as they were accessible to decision-makers. In some cases, insights never made it to fancy dashboards, but they reached decision-makers quickly. In other cases, already existing platforms were repurposed to fit Covid-19 needs. A few examples here are platforms like DHIS2 that developed ready-to-install digital data packages to support Covid-19 surveillance & response based on WHO guidelines. Another example is Ushahidi, which developed a dashboard component tracking cases of Covid-19 and other resources, supplies and services, and news. Ushahidi also set up internet hotspots to host information centres that helped disseminate educational and health information (videos, pdfs and audios) to help people navigate challenges caused by the pandemic.

Data collected by private practitioners for their day to day operations played a vital role in enabling analytics that accessed the social and economic impact of Covid-19. For example, mobile phone data for mobility tracking was widely reused with examples in Ghana, Sierra Leone, DRC, Gambia, and Namibia. Another example of private sector data reuse was Yoco Financial data that the company repurposed to assess the effect of Covid-19 on small businesses turnover.

These examples have illustrated that what is needed in a time of crisis is not only new technologies and platforms but already working solutions and leveraging existing links (collaborations). An additional key to this success was the speed of executions anticipating and dealing with changing needs as stakeholders got on board with data-driven solutions.

The agenda on data use was a priority for everyone.

The joint UN statement on data protection and privacy in the Covid-19 response statement states that the collection, use, sharing and further processing of data can help limit the spread of the virus and aid in accelerating the recovery, primarily through digital contact tracing. There has been evidence of an increased enthusiasm with which people tried to mobilize around new data sources or accessing existing information which has portrayed the level of value attached to the use of data for crisis response. One way that the agenda on data was pushed was by forming national Covid-19 task forces on data which mobilized relevant stakeholders and national leaders to unfasten critical roadblocks to data sharing and access to coordinate and advance the crisis response. The galvanized interest around data also made several analyses possible faster than it would have been in a different case.

All the above worked even though in Africa, we are faced with a data ecosystem that is still maturing, and that hasn’t yet worked through a lot of the issues around data governance and use. These include: how to navigate the vast regulatory burden that makes the subject of data access and sharing sensitive, how to operate within unclear legal frameworks (what should be public and not, which leaves solutions hidden from people that would benefit from them) and how to ensure data is privacy-safe but still useful for the analysis.

To address these issues there is a need for various interventions, including; building capacity to develop data-enabled solutions and to address data needs, addressing the gaps in data sharing laws, mechanisms and policies, and creating institutional and technology infrastructures to unlock access and enable effective data sharing and policies across public institutions. While there is noticeable progress caused by the united stand that has been towards responding to Covid-19, there remains work to do if Africa is to harness the benefits of data in policy responses.

So, it’s true, the novelty and urgency of the pandemic brought about openness and a learning appetite (about new approaches, interest in the new ways of doing things which fostered data innovations), and there is a lot that we can learn from the various examples done across Africa to improve data innovation for social good, beyond Covid-19.

However, if we are truly going to say that covid-19 has been a catalyst for data-enabled innovation, we need to ask: How do these lessons tie into the policy requirements of data access and use? This is the next question we are answering through this project.

The findings in this article are a result of a conversation from real-world experiences shared during the “Data sharing for Covid-19 response: lessons from African experiences for the development of data policy” (20th October 2021) focus workshop convened under the DSA visiting fellowship program, to support the project “Increasing Data Sharing from Africa’s Covid-19 Response”.

Great thanks go to everyone who participated in the workshop and the Data Science Africa team for the support and Jessica Montgomery and Prof. Neil Lawrence for the overall guidance on this project.

Reach out to: Morine Amutorine